Building an ARMy of Xen unikernels

By Thomas Leonard - 2014-07-22

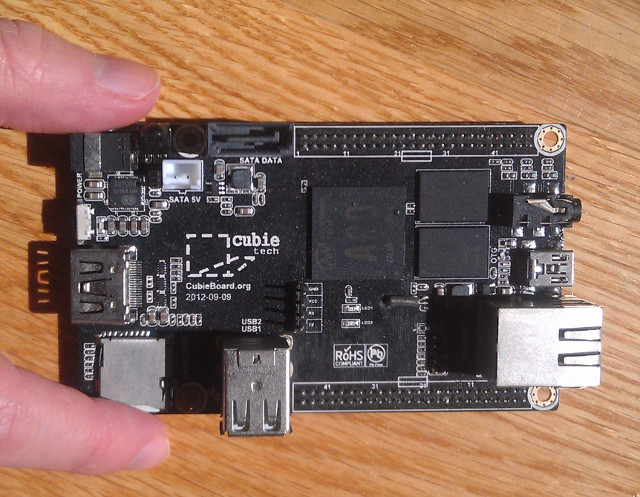

Mirage has just gained the ability to compile unikernels for the Xen/arm32 platform, allowing Mirage guests to run under the Xen hypervisor on ARM devices such as the Cubieboard 2 and CubieTruck.

Introduction

The ARMv7 architecture introduced the (optional) Virtualization Extensions, providing hardware support for running virtual machines on ARM devices, and Xen's ARM Hypervisor uses this to support hardware accelerated ARM guests.

Mini-OS is a tiny OS kernel designed specifically for running under Xen. It provides code to initialise the CPU, display messages on the console, allocate memory (malloc), and not much else. It is used as the low-level core of Mirage's Xen implementation.

Mirage v1 was built on an old version of Mini-OS which didn't support ARM. For Mirage v2, we have added ARM support to the current Mini-OS (completing Karim Allah Ahmed's initial ARM port) and made Mirage depend on it as an external library. This means that Mirage will automatically gain support for other architectures that get added later. We are currently working with the Xen developers to get our Mini-OS fork upstreamed.

In a similar way, we have replaced Mirage v1's bundled maths library with a dependency on the external OpenLibm, which we also extended with ARM support (this was just a case of fixing the build system; the code is from FreeBSD's libm, which already supported ARM).

Mirage v1 also bundled dietlibc to provide its standard C library.

A nice side-effect of this work came when we were trying to separate out the

dietlibc headers from the old Mini-OS headers in Mirage.

These had rather grown together over time and the work was proving

difficult, until we discovered that we no longer needed a libc at all, as

almost everything that used it had been replaced with pure OCaml versions!

The only exception was the printf code for formatting floating point

numbers, which OCaml uses in its printf implementation.

We replaced that by taking the small fmt_fp function from

musl libc.

Here's the final diffstat of the changes to mirage-platform adding ARM support:

778 files changed, 1949 insertions(+), 59689 deletions(-)

Trying it out

You'll need an ARM device with the Virtualization Extensions. I've been testing using the Cubieboard 2 (and CubieTruck):

The first step is to install Xen. Running Xen on the Cubieboard2 documents the manual installation process, but you can now also use mirage/xen-arm-builder to build an SDcard image automatically. Copy the image to the SDcard, connect the network cable and power, and the board will boot Xen.

Once booted you can ssh to Dom0, the privileged Linux domain used to manage the system, install Mirage, and build your unikernel just as on x86. Currently, you need to select the Git versions of some components. The following commands will install the necessary versions if you're using the xen-arm-builder image:

$ opam init

$ opam install mirage-xen-minios

$ opam remote add mirage-dev https://github.com/mirage/mirage-dev

$ opam install mirage

Technical details

One of the pleasures of unikernels is that you can comprehend the whole system with relatively little effort, and those wishing to understand, debug or contribute to the ARM support may find the following technical sections interesting. However, you don't need to know the details of the ARM port to use it, as Mirage abstracts away the details of the underlying platform.

The boot process

An ARM Mirage unikernel uses the Linux zImage format, though it is not actually compressed. Xen will allocate some RAM for the image and load the kernel at the offset 0x8000 (32 KB).

Execution begins in arm32.S, with the r2 register pointing to a

Flattened Device Tree (FDT) describing details of the virtual system.

This assembler code performs a few basic boot tasks:

- Configuring the MMU, which maps virtual addresses to physical addresses (see next section).

- Turning on caching and branch prediction.

- Setting up the exception vector table (this says how to handle interrupts and deal with various faults, such as reading from an invalid address).

- Setting up the stack pointer and calling the C function

arch_init.

arch_init makes some calls to the hypervisor to set up support for the console and interrupt controller, and then calls start_kernel.

start_kernel (in libxencaml) sets up a few more features (events, malloc, time-keeping and grant tables), then calls caml_startup.

caml_startup (in libocaml) initialises the garbage collector and calls caml_program, which is your application's main.ml.

The address space

With the Virtualization Extensions, there are two stages to converting a virtual memory address (used by application code) to a physical address in RAM. The first stage is under the control of the guest VM, mapping the virtual address to what the guest believes is the physical address (this address is referred to as the Intermediate Physical Address or IPA). The second stage, under the control of Xen, maps the IPA to the real physical address. The tables holding these mappings are called translation tables.

Mirage's memory needs are simple: most of the RAM should be used for the garbage-collected OCaml heap, with a few pages used for interacting with Xen (these don't go on the OCaml heap because they must be page aligned and must not move around).

Xen does not commit to using a fixed address as the IPA of the RAM, but the

C code needs to run from a known location. To solve this problem the

assembler code in arm32.S detects where it is running from and sets up a

virtual-to-physical mapping that will make it appear at the expected

location, by adding a fixed offset to each virtual address.

For example, on Xen/unstable, we configure the beginning of the virtual

address space to look like this (on Xen 4.4, the physical addresses would

start at 80000000 instead):

| Virtual address | Physical address (IPA) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 400000 | 40000000 | Stack (16 KB) |

| 404000 | 40004000 | Translation tables (16 KB) |

| 408000 | 40008000 | Kernel image |

The physical address is always at a fixed offset from the virtual address and the addresses wrap around, so virtual address c0400000 maps back to physical address 0 (in this example).

The stack, which grows downwards, is placed at the start of RAM so that a stack overflow will trigger a fault rather than overwriting other data.

The 16 KB translation table is an array of 4-byte entries each mapping 1 MB of the virtual address space, so the 16 KB table is able to map the entire 32-bit address space (4 GB). Each entry can either give the physical section address directly (which is what we do) or point to a second-level table mapping individual 4 KB pages. By using only the top-level table we reduce possible delays due to TLB misses.

After the kernel code comes the data (constants and global variables), then the bss section (data that is initially zero, and therefore doesn't need to be stored in the kernel image), and finally the rest of the RAM, which is handed over to the malloc system.

Contact

The current version seems to be working well on Xen 4.4 (stable) and the 4.5 development version, but has only been lightly tested. If you have any problems or questions, or get it working on other devices, please let us know!